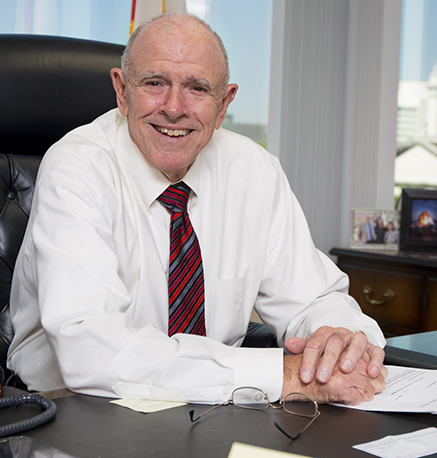

Willie Meggs ('76)

Leaving a 50-Year Legacy

When William N. “Willie” Meggs retires in December as state attorney for the Second Judicial Circuit of Florida, he will have spent more than 40 years prosecuting cases for the office.

When William N. “Willie” Meggs retires in December as state attorney for the Second Judicial Circuit of Florida, he will have spent more than 40 years prosecuting cases for the office.

Meggs has been around courtrooms for even longer. He began his career in law enforcement, taking undergraduate classes at Florida State while working full time. After being promoted to detective and investigator, Meggs found himself testifying in court frequently.

“I was down at the courthouse regularly,” recalled Meggs. “We spent a lot of time with grand juries, we spent a lot of time testifying at trials and those sorts of things. And I was watching the prosecutors, saying, ‘I could do that.’ But I had an impediment – I didn’t have a law degree.”

Meggs enrolled at the College of Law, painting parking lots to pay for classes. He interned at the State Attorney’s Office while a student and spent many hours researching in their library, which translated into a job offer a week before he graduated in 1976. Meggs still drinks coffee from a mug that belonged to former State Attorney Harry Morrison, who hired Meggs.

Other than a brief time after Meggs left the State Attorney’s Office in 1983 to campaign, that office is the only place Meggs has ever practiced law.

"I resigned and opened up a little private practice, and I did pretty well. I operated out of my pickup truck and a local lawyer gave me a little space in the basement of his office where I could hang out. I was doing okay, but I was running,” said Meggs, whose first of eight terms as state attorney began in January 1985.

Meggs does not try many of the cases for which his office is responsible, but he is certainly involved in them. No one seeks the death penalty without consulting Meggs and he attends the vast majority of his office’s grand juries. Meggs spends much of his time talking to people about the cases against them.

“I’d like to tell you that I do all the big things like the murder cases, but I’m dealing with people beating up other people and stealing checks and the reason I do that is there is so much misunderstanding by people about the law and nobody ever takes the time to talk to them,” said Meggs, who has banned voicemail in his office and insists that every call be answered. “So I end up talking to people – defendants, their mamas, grandmamas, employers – and we try to figure out the right thing to do with their case. We hold them accountable, but we try to help them. I always answer my phone when it rings and I spend most of my day dealing with people with problems.”

Although Meggs has spent his career trying to get convictions for the state, he is proud that his office has helped many people.

“There are tons of people that you can help and we do,” said Meggs. “I put a lot of people in a program called Teen Challenge because of their drug or alcohol problems. I honestly spend more of my time helping people and dealing with their cases in a responsible manner to keep from prosecuting somebody that doesn’t need to be prosecuted. I’ve tried to instill in our people that if you can help somebody, for goodness sake, help them.”

According to Meggs, the Teen Challenge program, which is actually for adults, has prompted many people who were battling with addiction to transform their lives.

Although Meggs has handled many complex and high-profile cases, one of his most cherished cases is one he took to help a homeless man.

“One of the cases I’m most proud of is a case that we lost; we ended up getting hung juries on the case and we eventually lost it,” recalled Meggs. “But, it was a case that nobody cared about. It was a homeless guy that got beat up and robbed and he had no family. He had nobody going to bat for him. Nobody would have said anything had we dropped it. We could have dropped it after we hung the first time, the second time and third time. We finally lost it on the fourth time, but we tried it because it was the right thing to do. I’m pleased that we kept going. It was a low profile case, versus a high profile case, but it got the same attention from our office.”

Every decision Meggs makes stems from wanting to do the right thing. He has spent numerous hours training young lawyers on ethical issues, encouraging them to treat everyone equally and with respect. Many of those lawyers have been FSU graduates, as Meggs hires from the College of Law regularly. Meggs is proud that many FSU law students gain valuable work experience in his office, just like he did as an intern more than four decades ago. Meggs still remembers vividly his first jury trial, which was during the first week of his internship.

As he reflects on his law career, Meggs knows now is the right time for him to retire.

I’m 73 years old and in April I started my 50th year of being in law enforcement and that’s a pretty long time to be in this business,” said Meggs. “I’m here every day and I plan to be here every day until this term is up. I work very hard and I enjoy every day. I enjoy the people I work with; I think we’re making a difference. But, I think you need to know when it’s time to quit and I just think it’s time.”

When he leaves, Meggs will have more time to “fool” with his horses. He’s been around the animals for 50 years and serves as a foster parent for abused horses.

“I like to ride and most of the things that are wrong with me today are because of horses – I limp and had broken ribs,” joked Meggs, who currently has four horses. “Mostly that was my fault.”

He also looks forward to spending more time with family. Meggs and his wife of 49 years, Judy, have three children and five grandchildren who live in Tallahassee and visit almost every weekend for Sunday dinners. His oldest daughter, Trisha, is a lawyer at the Attorney General’s Office, his son, Wiley, is a deputy sheriff sergeant, and his youngest daughter, Neeley, is a deputy sheriff. His grandchildren range in age from 5 to 15 and can often be found riding horses at Meggs’ house, which is on 60 acres and includes a barn.

“I really like land and I’ve got tractors and backhoes,” said Meggs, who admits he would have liked to have been a farmer, so retirement will be his chance to somewhat live that lifestyle. “Mowing my pasture and operating my tractor is my therapy. I’m at peace with the world when I’m on my tractor.”

As printed in the spring 2016 issue of Florida State Law magazine.